Pursing a graduate degree requires discipline and confidence. It is a process that also requires commitment and sustained interest. Doctoral degrees in particular, demand something more than an interest in attaining another credential. You need to be personally invested in the new knowledge you create. Creating new knowledge is a process that simultaneously exposes us and emboldens us. Part of the graduate school process is about developing and refining your intellectual identity. This is best done by knowing your intellectual value before entering graduate school.

Knowing your value can be a challenge to women and members of other groups over whom society has cast doubt. Many of us spend our lives trying to adapt to or mold ourselves into someone other than who we are, because we doubt that we bring value to relationships, careers, and classrooms. We do this to please an employer or a client, a family member or spouse, friends and acquaintances. Many of us have done this to survive. Though we may strive to bring our whole confident selves with us everywhere we go, women are trained from an early age to please, placate, and reassure everyone but themselves.

I’m made hopeful, however, when I speak to older women who tell me they couldn’t care less about what people think about them. As they age, the angst and self-consciousness seemingly melts away. They speak bolder, and wear what they please. I haven’t yet learned how to activate that invisible cloak which grants immunity to criticism. Instead, I’ve focused on lessons learned from my life experience (professional and personal) to validate myself, particularly in graduate school. The most effective method of fortifying myself has been in accessing ancestral spirits and histories. Some of these are ancestors are related to me by blood. Others are not. All of these women trusted their own vision and voice. Women like Zora Neale Hurston. Shirley Chisholm. Sojourner Truth.

Over a 165 years ago, Sojourner Truth started a career as a public intellectual and activist at 50 years of age. Unable to read and write, she worked among learned abolitionists, feeling vindicated by her personal, spiritual revelations. Truth believed she was called by the “holy spirit” to travel and speak on behalf of women and enslaved peoples throughout the United States and the world. The speech for which she is best known, (which is far different than the Ain’t I A Woman version that is more like folklore), tells us the basis upon which she made her claim for women’s equal rights. The anti-slavery newspaper, the Bugle’s, account of Truth’s May 29, 1851 speech at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, reads in part (emphasis mine):

“One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the convention was made by Sojourner’s Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity.

“May I say a few words? Receiving an affirmative answer, she proceeded; I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights [sic]. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if woman have a pint and man a quart—why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much—for we won’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seem to be all in confusion and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble. I can’t read, but I can hear. I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again…. “

This is obviously filled with a number of problematic assumptions about gender roles (pint vs. quart?). But we see a very strong, womanist statement on equity that interrupts business as usual. Having engaged in the back breaking labor the same as a man did, she asked crowds over and over again why she, a Black woman should be considered any less human? There’s no mention of 13 children, no broken southern dialect. Instead, the author dictates a reasoned argument (rooted in popular religious thought of the day) spoke in broken Dutch by a Black woman born in upstate New York.

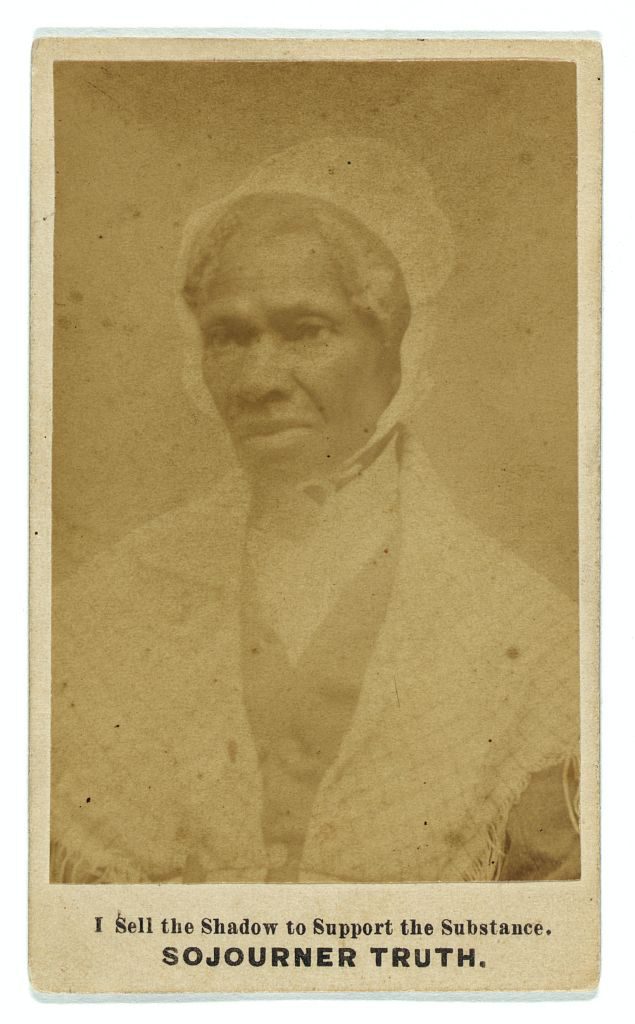

Just three years after Seneca Falls, Sojourner Truth was black, a woman, a former slave who simultaneously disrupted the suffragist and abolitionist movements and lived her self-consciously intersectional life before that term or even the concept of feminism was in vogue. She brought her very body, memory, and reasoning. Her approach to being a public intellectual was unorthodox. She was an expert witness to white supremacy who carried the truth in her body, dictated it to her biographer, and shouted it from podiums. Sojourner Truth, born Isabella, found a way to finance her work, using her own image. She sold photos of herself with caption that read, “I sell the Shadow to support the Substance.” She operated from her substance, her intellect.

Scholars and intellectuals like Truth disrupt, interrupt, and turn conventional thinking on its head, shift debates, and redirect attention. To be an intellectual, a scholar, is to do just that, move minds and spirits. We can do that in any number of ways. We can do it with our stories, our bodies, and our presence. Too often, we dismiss what we bring to the public sphere or academia as not being deemed intellectual or scholarly due to the language we use, our age, class status, or traumatic life experiences that have chastened us. If Truth had accepted others’ definitions her, she never would have achieved all that she had her in her life on behalf of her family, women, her faith, and enslaved peoples. Her very presence, body, and life story were her scholarly contributions. I am sure she doubted herself.

Many of us are trapped in self-doubt. I’ve engaged in some of this doubtful, inner questioning while pursuing my PhD. Am I in the correct academic discipline? Is this the right way to approach this topic? Does my work contribute anything new to the field? Even though, I had two impressive degrees and a fair amount of practical experience in my field, I still worried that I was being overshadowed by younger colleagues with a better command of the academic “language” of the discipline. Yes, I had worked in city planning for years (without calling it that), but the way the discipline was discussed in academia was very different than I had experienced it as public administrator and manager.

At first glance, it might appear that I had the advantage over younger colleagues with less professional experience. However, in an academic setting, translating your past to the present can be tricky. How many of your ideas and approaches come from antiquated notions? How many road blocks are really opportunities for you break through barriers, break ceilings? In a PhD program, knowing how much life experience to bring to your work while making room for new theories and ideas is a delicate balance particularly for older women, women of color, or any manner of nontraditional student in graduate school. The rollercoaster of emotions can go from feeling misunderstood and undervalued to sensing that people perceive you as an imposter.

That’s why doing a self-assessment before deciding to pursue graduate school is important. It is important to focus first on what you bring to the academic community rather than whether or not you fit into an academic community. you need a process that forces you to document your intellectual baggage and your bravery. Then you can invite into the assessment process whomever YOU desire to be a witness to that account. Share your “shadow” and your substance on your own terms.

So how do you assess your intellectual value and scholarly identity? I recommend a life achievement log or timeline. It isn’t really a timeline as much it is about looking to seminal moments of your life and viewing them through the prism of these questions during four phases: ages 16-22, 23-34, 35-45, and 50-65. Adjust these phases as you see necessary. The idea is to examine any patterns in your thinking and approaches to creativity, problem solving, and discovering opportunity. These are all the ingredients of an intellectual identity. In your applications to graduate schools, for example, they will be looking for this intellectual or scholarly identity.

Begin by answering these questions in three spheres: personal and professional relationships, your personal milestone, and professional milestones. Our intellect operates in and across all these spheres. Also recognize how you have already been operating as an intellectual. Here are a few questions to help guide the process:

- What are the biggest challenges I have encountered?

- Why did I fail or succeed? What are the assumptions and thought patterns that served me, or didn’t?

- And if I succeeded what was unique about my approach to addressing the problem or obstacle? Did I use a different set of tools, rationale, or different “recipe” than those around me?

- Finally, when and why were you frustrated with other people’s inability to “see” an opportunity to make change? How did you respond?

- Make a list of your intellectual, moral, or scholarly guardian angels. Note which of their ideals and aspects of their characters you have incorporated into your personal and professional life.

I also recommend recording your answers in a way you that’s comfortable for you, but that is easily accessible. You will need this information when developing your statements of purpose in applications to academic programs. You may want to jot down notes in a diary, record thoughts with a digital recorder, paint, or make a video. If you make a video, please share it with me. I’d love to see how this process works for you.

For more on Sojourner Truth, one of my intellectual, guardian angels. Read a great overview of Nell Painter’s seminal work on Sojourner Truth, in the article

In search of the truth: Sojourner Truth

Link: http://www.dailykos.com/story/2016/5/29/1530281/-In-search-of-the-truth-Sojourner-Truth

Also listen to Nell Painter’s C-Span interview about the book: http://www.c-span.org/video/?77043-1/book-discussion-sojourner-truth-life-symbol

If you need help mapping out your road to graduate school as a mature woman, as a woman of color, or someone who has been away from academia a long time, contact me. I ‘d love to see how I can be an ally during your journey.

About Dr. Andrea Roberts

Andrea is a planning and historic preservation professional and founder of the Texas Freedom Colonies Project. She returned to graduate school after ten years working in public finance, housing, economic development, grassroots advocacy, and nonprofit management in Houston, Philadelphia, and other metropolitan areas. Offering “graduate guidance” is one way she hopes to make the reentry process for those returning to academia after a long hiatus a little easier than it was for her. Her academic prep services have been developed with women of color and mature women in mind. Andrea holds a MA in Governmental Administration and Public Finance from the University of Pennsylvania and a BA in Political Science and Women’s Studies from Vassar College.

Contact (email link): Andrea Roberts

Facebook Group: Is A PhD or me?