That should never have happened. The destruction of Macy’s (formerly known as Foley’s), is a stab in this antiquarian’s heart. Not just because I like old things and am sentimental. I own all of that and try to make some use of that disposition. Lot of articles go on and on about fond memories of Macys’ when it was Foley’s. I have a few of those memories of well, but what troubles me more is the lack of attention to the historic nature of the exterior and interior of the building. The demolition strikes me as a pivotal moment in Houston’s architectural, historical, and cultural history.

Here’s why.

First, its an amazing example of modern architecture. You can see more about how architect Kenneth Franzheim’s work shaped downtown Houston here: http://digital.lib.uh.edu/collection/franz There are great architectural drawings there too. His buildings preceded the Astrodome as one of Houston’s great emblems, landmarks of its identity as a shiny new, modern City.

Foley’s/Macy’s, Downtown Houston

Secondly, and I argue most notably, the demolition marks the destruction of a significant piece of local and national Civil Rights history destroyed in the name of development in downtown Houston. Foley’s, later purchased by Macy’s was one of the few sites of national Civil Rights history in Houston integrated into the mainstream landscape, and now it is gone.

The University of Houston’s Foley’s archives are an amazing testament to the role of the company in Houston history.

It includes several items offering insights into how desegregation was integrated into its corporate history and the overall vision of downtown Houston. You’ll note interesting items in Box 16 in the archives:

- Folder 7: Legal Issues-Max Factor, 1960

- Folder 8: Legal Issues-Trademark Issues (Also See OVS), 1960

- Folder 9: Legal Issues-Lockett, Lockett & Brady, 1960

- Folder 10: Stairways in Foley’s Sharpstown Branch, 1960

- Folder 11: Speech by Mr. Levine, 1960

- Folder 12: Executive Biographies, 1960

- Folder 13: Federal Trade Commission, 1960

- Folder 14: Advertising Reversals, 1960

- Folder 15: Lease Agreements, 1960

- Folder 16: Newspaper rates, 1960

- Folder 17: Foreign Fair (also see OVS), 1960

- Folder 18: Brown Shoe Company, 1960

- Folder 19: Integration-Integration Magazine Articles, 1960

- Folder 20: Integration-God the Original Segregationist, 1960

- Folder 21: Integration-The Negro Market (Analysis from 1954), 1960

- Folder 22: Integration-The Negro Labor News, 1960

- Folder 23: Integration-Desegregation of Eating Facilities

- Folder 24: Transportation-The Truth about Our Freeways, 1960

- Folder 25: Transportation-Urban Transportation Books, 1960

- Folder 26: Transportation-Houston-Harris County Transportation Plan, 1960

- Folder 27: Leading Dept. Store newspapers advertisers, 1960

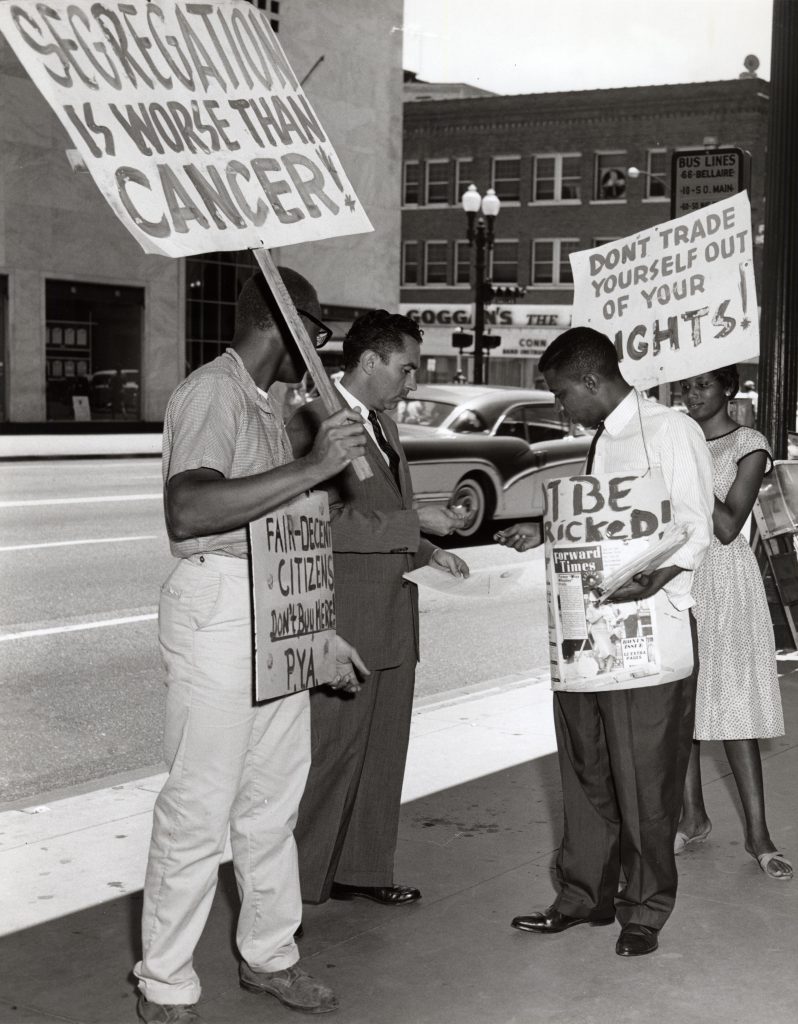

Here’s one of those photos:

These archives and the excellent documentary film, “The Strange Demise of Jim Crow” talk about the desegregation process, contains riveting interviews with then TSU student activists, and details the associated media black out engineered in party by Bob Dundas, vice president of Foley’s downtown department store. I highly recommend it, as I only scratch the surface of Houston’s civil rights struggle in this post. here’s a very short, yet informative excerpt:

There was an intense sit in and demonstration movement among African Americans students in Houston during the 1960s, but a black out and purposeful suppression of this history persisted until the 1990s. In March of 1960, students held sit ins at Weingarten supermarket. Daily sit ins at Foley’s lunch counters (yes they had lunch counters) followed.

In “Silent Transformation in the Bayou City: The Desegregation Process of Houston’s Public Facilities, “ the author sites Thomas Cole’s , No Color Is My Kind, a book consisting of sit in leader Elderway Stearns’ accounts and UH Foley’s archives explains the business and media establishment’s very deliberate manipulation of media coverage rooted in fear associated with the 1917 riots:

After much effort, he got local downtown merchants to agree to desegregate their lunch counters all simultaneously on the condition that there would be no press coverage of the event. Dundas got together with John T. Jones, publisher of the Houston Chronicle and president of Houston Endowment, and they worked to make sure that the event would not receive any news coverage. Oveta Culp Hobby, owner of the Houston Post, agreed to their plan, and under threats to pull Foley’s advertising from the Houston Press, Editor George Carmack also agreed to Dundas and Jones’ plan. They secured an agreement between local newspapers and radio stations to remain silent on the event for ten days.[20] On August 25, 1960, seventy Houston lunch counters quietly integrated and Dundas greeted the TSU students when they arrived at Foley’s lunch counter and asked for service.[21] The growing fears of racial violence led the white power elite to voluntarily desegregate and the result was a peaceful, relatively unnoticed social change in Houston.”

Silent equals safe. Silent equals “we have our Negroes under control here.” This perception of Black – White relations have canged but in some ways persisted. Foley’s was a point of origin, a blueprint for a powerful myth.

Foleys is now a ruin. It was one of a few sites holding public history and material culture of Houston’s shadow governments, white citizens’ councils and others who acted under euphemisms and the guise of business associations, and in back rooms. This legacy, this intangible culture, is one of a very few elements of the Houston landscape that disputes the hegemonic “Negro complacency” construct perpetuated by business and government in 1960. This same story of happy, complacent Blacks is peddled to this day, though less effectively. However, today’s newcomers attribute to African American Houstonians this same characterization. As a result, a history of Black resistance is a surprise to newcomers, who wonder why these African Americans never employed agency or protested like Black people in Little Rock and Birmingham. The media silence of 1960 morphs into the silence of my youth in the 1980s where Juneteenth became one of the few sanctions expressions of Blackness but still absent explicit resistant (though cultural preservation is a form of resistance). Then later, again becomes the silence of newcomers, wondering about those “quiet”, “passive” Houston Negroes. Much is hidden in this silence.

This demolition is yet another example of what I write about in much of my personal writing, this blog, and my doctoral work. Much of it falls under what Foucault called an “archaeology of silence.” This is a figurative archaeology mind you, but an apt name for a phenomenon with tangible, real world consequences hidden beneath the dermis of public history, memory, and life. The phrase describes one of the most insidious exercises of power, the power to induce forgetting without anyone knowing exactly how or why. More than forgetting, it is an unreason, an unknown voice of subjects treated only as objects in discourse. The persistent visible madness (racism, racial terrorism, suppression, oppression, apartheid/Jim Crow) inhibits organizing and consciousness-raising, across state and socially constructed divides. The invisible madness is that characterization of other, lost voices. Such as that of the protesters’ memory of the building and its meaning, now reduced to rubble. The building was a portal, a passage way to a very important opportunity — to excavate the African American agent, protester, resister from the ruins of an endangered downtown Houston.

Here’s a short video about what 1960 was like for TSU students attempting to integrate lunch counters throughout the City. Remember them and remember Foley’s/Macy’s.