Texas had their own Zora Neale Hurston, but who knows his name, remembers where he lived?

During my work on the Austin Historical Survey Wiki Project, I came across this home in East Austin. You’d pass it or see it and think it was simply an eyesore, a casualty of urban neglect. There’s no roof and it is surrounded by barbed wire. But this is no ordinary East Austin home. This is the home of JOHN MASON BREWER and it needs desperately to be restored.

About BREWER, JOHN MASON (1896–1975), From Texas State Historical Commission Online.

John Mason Brewer, black folklorist, son of J. H. and Minnie T. Brewer, was born in Goliad, Texas, on March 24, 1896. His sister, Stella Brewer Brooks, an authority on Joel Chandler Harris and the Uncle Remus tales, shared his interest in folklore. Brewer attended the black public schools in Austin and in 1917 received a B.A. from Wiley College in Marshall. He joined the army in 1918, became a corporal, and spent a year in France as an interpreter (he spoke French, Spanish, and Italian). He then returned to a career as a teacher and principal in Fort Worth. He eventually moved from secondary schools to colleges. He was working for an oil company in Denver, Colorado, when he began writing stories and poems, first for the company trade journal and later for a monthly journal called The American Negro. In 1926 he was a professor at Samuel Huston (now Huston-Tillotson) College in Austin, where he met University of Texas professor J. Frank Dobie, who influenced him to turn from publishing his own poetry to collecting and publishing black folklore. In 1950 Brewer received an M.A. from Indiana University, and in 1951 an honorary doctorate from Paul Quinn College in Waco. He was a Methodist and Democrat, with political friends as diverse as Governor Allen Shivers and President Lyndon B. Johnson.qqv

East Side Home of Folklore legend, J Mason Brewer

Steps leading to the home of J. Mason Brewer in East Austin

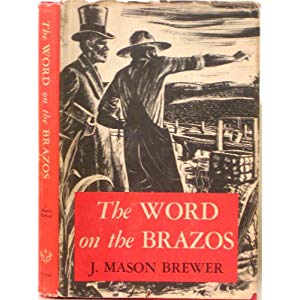

Brewer’s list of “firsts” is impressive. As the first black member of the Texas Folklore Society he addressed its meetings and published in six of its annual volumes. He became the first black member of the Texas Institute of Letters in 1954, after being chosen one of twenty-five best Texas authors by Theta Sigma Phi, for The Word on the Brazos: Negro Preacher Tales from the Brazos Bottoms of Texas. He was the first black to serve as vice president of the American Folklore Society. He received grants for research in Negro folklore from the American Philosophical Society, the Piedmont University Center for the Study of Negro Folklore, the Library of Congress, the National Library of Mexico, and the National University of Mexico. He has been compared to Zora Neale Hurston, a black writer who was part of the Harlem Renaissance. Like her, he was noted for his use of black dialects. He eventually became nationally known as a folklorist and popular lecturer and was included in Who’s Who in America the year after he died.

Brewer’s major books are The Word on the Brazos, Aunt Dicy Tales (1956), Dog Ghosts and Other Negro Folk Tales (1958), Worser Days and Better Times (1965), and an anthology, American Negro Folklore (1968), for which he won the Chicago Book Fair Award in 1968 and the Twenty-first Annual Writers Roundup award for one of the outstanding books written by a Texas author in 1969. Notable among several early volumes of poetry and history are Negrito (1933) and Negro Legislators of Texas (1936); both were reprinted in the 1970s.

After ten years of teaching at Livingston College in North Carolina, Brewer returned to Texas and finished his career at East Texas State University in Commerce, where he was distinguished visiting professor from 1969 until his death. He died on January 24, 1975, and was buried in Austin, leaving his second wife, Ruth Helen, of Hitchcock, Texas, and a son by his first wife. A short film on Brewer’s life was made in 1980 by the Texas Folklore Society and the Texas Commission on the Arts and Humanities.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

James W. Byrd, J. Mason Brewer: Negro Folklorist (Austin: Steck-Vaughn, 1967). Who’s Who in America, 39th ed.).

I’m not the first person to see this home and believe it needs to be preserved. I think it should definitely be restored.